From Cloud Nine to Clubland

Dancing at a Rehoboth Beach gay bar led Joseph Swartz to Clubland

This article was written by Joseph Swartz.

“What are you doing, dude?” I said, glancing at my brother across the table.

Our family was enjoying a brunch at the Army and Navy Club in Washington, DC, a city where brunch was tantamount to religion. The Club always made a stellar showing, but perhaps too stellar on this particular day.

Josh, like a bomb specialist trying to cut exactly the right wire, was using a knife and fork to eat his bacon. “I don’t know,” he replied. “Can you even use your hands to do things in a fancy place like this?”

My response was simply: “It’s just bacon, man. Don’t overthink it.”

I’m a first-generation Clubland citizen, if you hadn’t already gathered. The people I grew up with weren’t doctors, lawyers or military officers, but rather were farmers, machinists, and enlisted men.

My first visit to the Club, where I’ve been a member for sixteen years, was for brunch with LTC Henry Thomas IV, his partner Kevin, and a group of Virginia Military Institute cadets in 2008. The Club’s exclusivity tempered by the democratic tradition of military service made for love at first sight. Over the years, its continued embrace of heritage without being hidebound; adapting to modern life while retaining its identity has kept the spark alive.

Hank and I had met that previous summer through Deuntay – a six-foot tall, Black man with zero percent body fat and a max bench press of 350 pounds – who I was enamored with on the dance floor at Cloud Nine Restaurant, a popular gay bar and dance club in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, where my family was vacationing.

Deuntay, a cadet at the Virginia Military Institute, was staying with Hank and Kevin for the weekend as many other gay and lesbian cadets had done during the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell era. Hank was among the founders of a Virginia Military Institute gay and lesbian alumni network that provided a safe space for then-closeted cadets enrolled at VMI.

I met Hank the morning after my fling with Deuntay. Simmering nude in his hot tub, he shared glimpses of his background while I sipped my coffee.

Born to a Southern patrician family, Hank was an upper-class Forest Gump – always wrapped up in major historical events, even if he wasn’t the main player – who witnessed the end of this family’s ancestral tenure on large farms and the slow gravitation towards major cities. Upon graduating from VMI in 1959, he served three tours in Vietnam, served in the Executive Office of the President of the United States, and garnered an Environmental Protection Agency appointment in the early days of its inception.

His tenure at the EPA included establishing policy for radiation standards which resulted in President Reagan nominating him as Assistant Secretary of Energy for International Affairs, a post primarily focused on nuclear policy. His post-political life coincided with the explosive growth of consulting firms in the 1980s & 1990s, which ended with him becoming a partner at AT Kearney until it was purchased by EDS in 1995.

Around this time, Hank came to accept his identity and live a more authentic life. His divorce, which was finalized in 1995, made history as it reached the Virginia Supreme Court which ruled that homosexual activities constituted cruelty in a divorce proceeding. As a result, the next few years were tumultuous, with Hank facing bankruptcy and constant financial troubles.

But this period also represented tremendous personal growth. Hank, who was once a member oft he country’s most conservative institutions, found himself opening his small apartment to AIDs patients wanting to see the AIDS quilt displayed. Through voluntering, during this time, Hank met Kevin, who would remain his partner until Hank’s passing in 2011. [Yes, this is correct.]

That year, I spent Thanksgiving in Rehoboth with Hank and Kevin. The following summer, besides introducing me to Clubland, the pair provided me with a relaxing place to study for the bar exam after graduating from the University of Minnesota Law School.

Over that summer, Hank indulged my curiosity in many ways. The most memorable being when Hank took me to my first three-martini lunch. After a surf and turf lunch, I had no option but to pour myself into bed. Days later, I phoned my grandmother, who had worked in the family’s real estate business during this era.

Convinced that my performance at lunch was a sign of a lack of stamina, I asked “How did anyone get work done?” I asked. “You didn’t,” she chortled, “You told your secretary to hold your calls and slept it off on the couch in your office.”

As a budding young lawyer with middling grades in 2008, I was not in the best position. Major multinational law firms were going under with the real estate sector, leading experienced attorneys to compete for the same contract review gigs I tried pursuing. Federal jobs weren’t much of an option either, as it would be an entire year before an offer arrived.

That year was one of constant drubbing. After working temporarily as an executive assistant at the Nuclear Energy Institute, my only employment option was an internship at a lobbying firm that paid $800 a month. The U.S. Army was sincerely my only option. So, within eight months, I completed Basic Training and Officer Candidate School, commissioning as an army artillery officer. There were five attorneys in my OCS company alone.

Months later, on a visit to Rehoboth, Hank presented me with a commissioning present: a Army and Navy Club member card with initiation and first year membership dues paid in full.

In more than fifteen years of membership at the Club, I’m always finding new things to admire.

The Club has persevered through many challenges that have been the death knell for numerous others while also retaining top talent and increasing wages over time. Shirley Norris, affectionately known as Ms. Shirley by members, is a testament to this as she has continuously been employed by the Club since January 1958.

It has provided me with an opportunity to experience Clubland via reciprocal visits which brought me to the now defunct Miami Surf Club and Pittsburgh Athletic Association; Augusta’s Pinnacle Club, Honolulu’s Pacific Club; Baltimore’s Center Club; Duluth’s Kitchi Gammi Club; St. Louis’ Racquet Club; Charlotte City Club; Oklahoma City and Dallas’ Petroleum Club; Fort Worth Club; and internationally Baguio Country Club in Baguio, Philippines; Gremio Literario in Lisbon, Portugal; and Circulo Ecuestre in Barcelona, Spain.

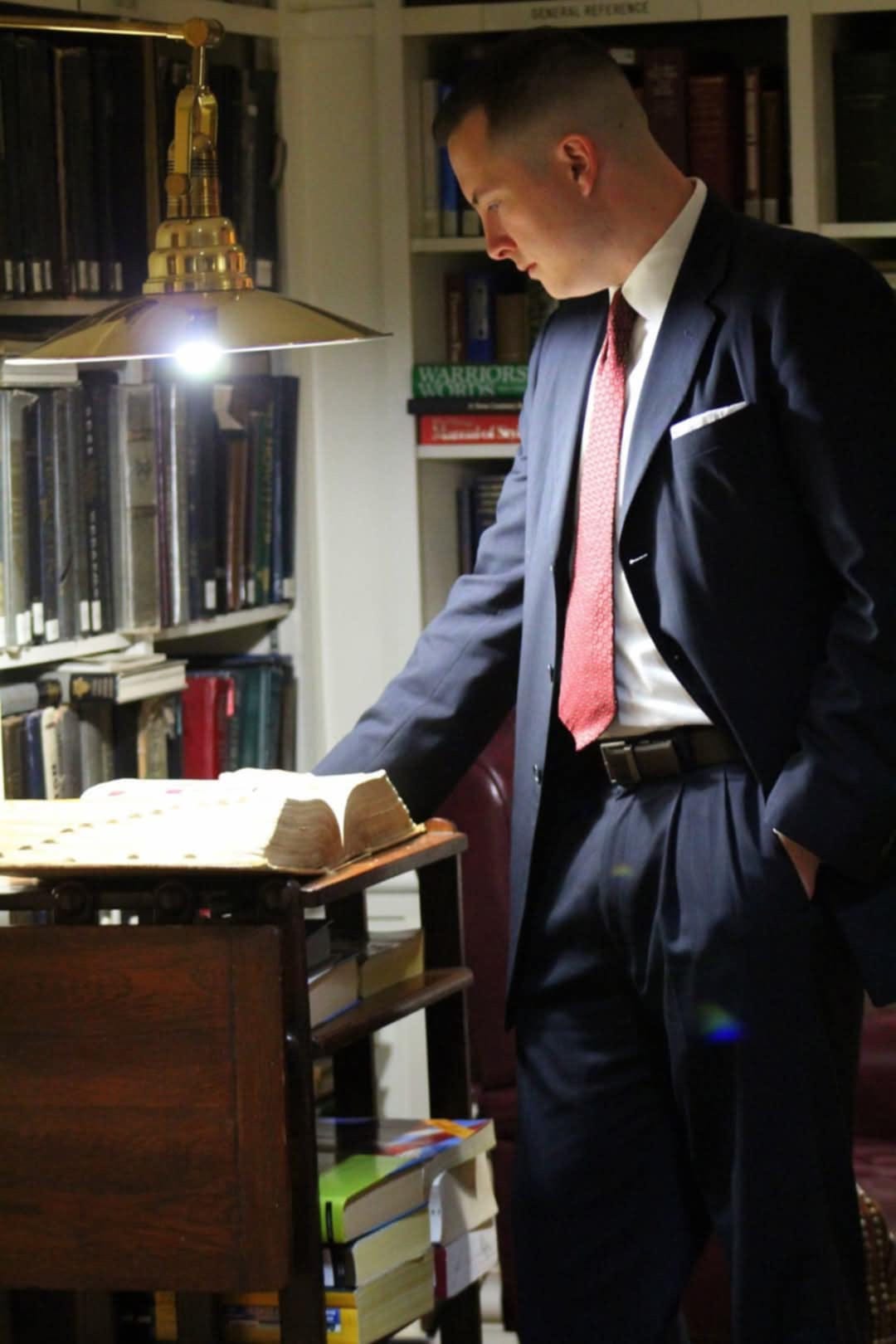

Much has changed since 2009 when I joined the Club. Cloud Nine has been demolished, Hank passed away while I was deployed to Afghanistan in 2011, and the bloom of my youth is beginning to fade. Though he and I fell out shortly before I deployed, I still think of him fondly. Little things at the club take me back to that time with him. The doormen’s greeting upon entry; the feel of the brass banister as I ascend to the second floor; the soft vitality of conversation in the Daiquiri Lounge; the first taste of a cold martini while I sit in the corner and wait for friends to arrive; the solemn silence of the library, sanctified by memorabilia of wars long past, my own generation’s collection now beginning to patina.

That sense of connection and tradition can’t be replicated outside of private clubs. Hank could have given me no greater gift than admitting me to Clubland, for which I will be forever grateful.