Clubland Heroes

“A man’s London club offers him a fortress,” writes Richard Usborne in a rather clubby book, aptly titled Clubland Heroes. “When Scotland Yard was baffled, inspectors … put through phone calls to Clubland members”. Usborne was writing about the West-End clubs of London. His heroes were fictional, drawn from the English writers Dornford Yates, John Buchan, and Sapper. “I have called this book Clubland Heroes,” Usborne explains, “because the heroes of the books I am examining were essentially West-End Clubmen, and their clubland status is a factor in their behaviour as individuals and groups”.

Usborne is the ever-so-pukka Clubman. He comports to his Clubland Heroes “the thinking of my class and age group, … about money, foreigners, leisure, killing, dogs, games, girls, and how to make love to girls, beer, champagne, Success, England, America, the lower classes, the upper classes, servants, and West-End Clubs”—though, if I’m being completely honest, I wouldn’t want to take advice on girls and lovemaking from a man who waxes nostalgic about “the Hall Porter of a man’s club” functioning as “a reasonable picket against women”.

Every club rat should have their club heroes. Stateside, my club heroes romp across Manhattan instead of St. James in London. We’ve got them all, but the two that I’ll focus on today are a war hero and a caustic writer.

Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885)

The United States—and the Union—was in a precarious position in 1862. The Civil War’s progress had been less than optimal and the Union was on no surer ground than it was at the beginning of the crises of Confederate secession. At the Sanitary Commission, a “war-born volunteer army of able and energetic humanitarians”, Frederick Law Olmsted (best known for Manhattan’s Central Park) and five other individuals floated the idea of mobilising private support toward the prosecution of the war. In 1862, their supporters started the Union League Club of Philadelphia; the following year, the Union League Club of New York was founded. On the day the Union League Club of New York’s clubhouse was opened to members, came the news of victory at Gettysburg, while “a little-known general named U. S. Grant had seized Vicksburg and control of the Mississippi”.

The Union League Club of New York has long prided itself on its association with Ulysses S. Grant. The Grant Room features portraits of Lincoln’s generals and of Edward Stanton, his Secretary of War, but is named for the most famous of them all—Grant. Last week, the Club marked the 203th anniversary of Grant’s birth, with General David Petraeus, and Grant historian H.W. Brands.

Ulysses S. Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio, in 1822. After he was sent up to West Point, Grant became an officer in the army and distinguished himself on the battlefield, first, during the Mexican-American War, and later, during the Civil War, where he was the commanding general of the Union Army. In 1869, Grant was elected, and subsequently reelected, as the eighteenth President of the United States.

As the commanding general of the Union Army, Grant was nominated to membership at the Union Club of New York, where he was excused from dues and enjoyed “special privileges” (what they are we do not know). Similarly, at the Union League Club, General Grant was given honorary membership, along with Abraham Lincoln, General William Sherman, Admiral David Porter, and others.

The Union Club and the Union League Club in New York both professed a heartfelt willingness to aid the Union during the Civil War. Immediately after the Union League Club of New York’s formation, they took it upon themselves to fund through subscription the raising of battalions and regiments of soldiers for the Union. Similarly, in 1864, ostensibly at Lincoln’s behest, the Union Club of Boston and the Union League Club of New York sent the Union League’s first president on a “business trip” to marshall the British aristocracy and government into support for the Union against the Confederacy.

Grant followed the presidency of Andrew Johnson, who was elevated to the presidency following Lincoln’s assassination. Johnson did much to prevent Reconstruction from being carried to fruition, but Grant’s presidency saw the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment—the last of the Civil Rights amendments to the Constitution—and pushed enforcement of the law against the newly revived and ascendant Klu Klux Klan. Not only did Grant push Reconstruction and Civil Rights in its early stages, perhaps more importantly, he was a symbol for national unity, bringing the nation together in a way that was bested only by Lincoln, Washington, and Jefferson.

Both as President and General, Grant was a formidable clubman who made the Upper East Side home after his time in the White House. We should be in awe of Grant, one of the men who single-handedly saved the Union.

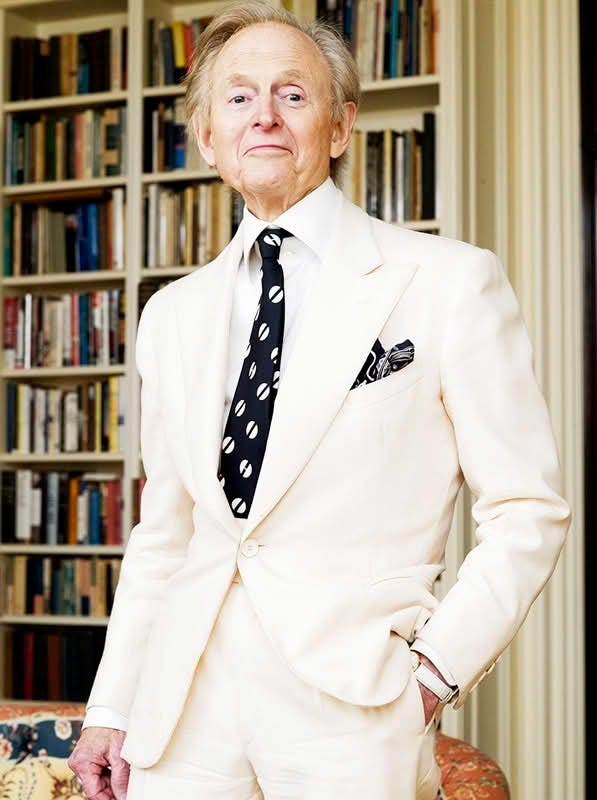

Tom Wolfe (1930–2018)

Wolfe was quite the character. Born in Richmond, Virginia, Wolfe moved to the Upper East Side at the height of his fame: he lived in a townhouse on 62nd St., between Second and Third Avenue, which he sold to obtain an apartment off Madison on 79th St. A long-standing member of the Union Club of New York on 69th and Park Ave—the oldest club in New York City!—Wolfe’s son, Tommy Wolfe, was a star squash player at squash mecca Trinity College, and the older Wolfe was well-known for dressing up in his trademark white suit, looking at Tommy play at the Union’s courts, of course, in a white polo and shorts, wielding a squash racquet with the same dexterity as his old man did a pen.

Wolfe was the caustic reporter who was responsible for New Journalism. At his best, he was piercing and scathing, and left little to the reader’s imagination, which was always lagging behind his rather colourful asides, glimpses into a truly great mind. While Wolfe commenced an academic career, writing an American Studies PhD dissertation at Yale, he never quite got the ivory tower; he was more content with making profoundly hilarious and undermining jabs at it.

In 1970, Wolfe turned his attention to fellow Upper East Sider Leonard Bernstein in what is perhaps some of my favourite writing from the twentieth century. Titled ‘Radical Chic’, the piece portrays a cocktail party at the composer Leonard Bernstein’s house, held in honour of the Black Panthers. Take, for instance, this rather silly but telling line: “When one thinks of Mitchell and Agnew and Nixon and all of their Captain Beef-heart Maggie & Jiggs New York Athletic Club troglodyte crypto-Horst Wessel Irish Oyster Bar Construction Worker followers, then one understands why poor blacks like the Panthers might feel driven to drastic solutions, and—well, anyway, one truly feels for them.” Whatever the troglodytes at NYAC did to earn Wolfe’s ire must’ve been rather dire.

On the other hand—I will admit this out of a pure selfishness—Wolfe’s quite impressed with the New Haven Lawn Club, and wrote in the same piece: “the way to sell anything was to show Harry Yale in the background, in a tuxedo, with his pageboy-bobbed young lovely, heading off to dinner at the New Haven Lawn Club.” I have yet to find the “young lovely”, but I do enjoy my dinners at the Lawn Club very much.

As art critic, the Painted Word (1975) features Peggy Guggenheim and her acolytes as ruining the art world through the introduction of theory, yet another jab at the pretensions of some to recast art in light of theory. Wolfe also wrote on architecture, and there, too, holding back wasn’t quite his forte.

The richness that Wolfe was able to describe upper class life in New York with, from their nostalgia de la boue, nostalgia for the mud, to the rather intricate yet flustering habits of arrivistas and the constant, ceaseless striving for status masked by an obdurate obsession with charity: you’ve got to assume as you walked into the Union’s bar or dining rooms that Wolfe was tending his own business rather quietly, whilst making some caustic and yet remarkably piercing remark about your foibles and failures and frustrations.

I’ve met some rather impressive club rats and some rather impressive Yale PhDs. I hope to be both myself, but Wolfe’s really where the bar is. Perhaps someday I’ll be a better writer, or finally develop a sense of style and wit beyond that which has been handed down to me, but for now, I’ve got to make do with equal measures of admiration and jealousy.